Spectroscopic Identification of Nitrogen- and Oxygen-Rich Polymeric Organics in Asteroid Bennu Regolith

Key Takeaways

- FTIR spectroscopy differentiates aromatic and aliphatic C–H bonds by detecting distinct vibrational bands, with CH₂/CH₃ intensity indicating aliphatic chain structure.

- STXM provides high-resolution chemical bonding information, complementing FTIR by resolving spatial and spectral ambiguities in N- and O-rich organic phases.

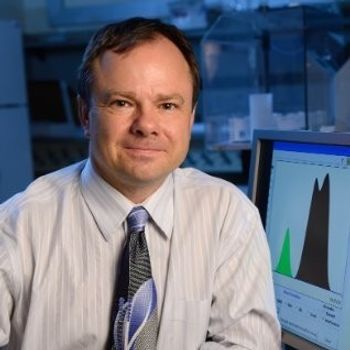

Returned samples from asteroid Bennu by the NASA OSIRIS-REx mission were analyzed using complementary spectroscopic and microspectroscopic techniques, including Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) microscopy (μFTIR), scanning transmission X-ray microscopy (STXM), and secondary-ion mass spectrometry (SIMS), revealing a previously unknown polymeric organic phase enriched in nitrogen and oxygen. Spectroscopy spoke to Scott Sandford and Michel Nuevo of NASA’s Ames Research Center (Moffett Field, California), and Zack Gainsforth of the University of California’s Space Sciences Laboratory (Berkeley, California), three of the authors of the paper (1) resulting from the research team’s analysis.

Returned samples from asteroid Bennu by the NASA OSIRIS-REx mission were analyzed using complementary spectroscopic and microspectroscopic techniques, including Fourier-transform infrared(FTIR) microscopy (μFTIR), scanning transmission X-ray microscopy(STXM), and secondary-ion mass spectrometry (SIMS), revealing a previously unknown polymeric organic phase enriched in nitrogen and oxygen. Infrared and X-ray spectroscopic signatures confirm extensive aqueous alteration and the presence of complex N-bearing organic matter, providing new insights into prebiotic chemistry preserved in carbonaceous asteroids. Spectroscopy spoke to Scott Sandford and Michel Nuevo of NASA’s Ames Research Center (Moffett Field, California), and Zack Gainsforth of the University of California’s Space Sciences Laboratory (Berkeley, California), three of the authors of the paper (1) resulting from the research team’s analysis.

How does Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy distinguish between aromatic and aliphatic C–H bonding in carbonaceous extraterrestrial materials, and what information does CH₂/CH₃ intensity provide about molecular structure?

The primary means of using FTIR spectroscopy to distinguish between aromatic and aliphatic CH bonding in extraterrestrial samples involves the detection of the C–H stretching vibrational bands of these two types of organic compounds. The aromatic C–H stretching feature falls as slightly higher frequencies (~3030 cm-1) than the corresponding aliphatic bands (2950–2825 cm-1). In addition, while the aromatic C–H stretching feature is usually a single band, aliphatic C–H stretching vibrations typically produce three or four subfeatures, depending on whether the stretching motion is in a –CH2– or –CH3 group and whether the mode is symmetric or asymmetric. The strengths of the various aliphatic subfeatures can be used to establish the relative abundance of –CH2– or –CH3 groups. The –CH2–/–CH3 ratio provides an indication about the overall structure of the aliphatics. Since –CH3 groups terminate an aliphatic chain, high –CH2–/–CH3 ratios imply relatively long aliphatic chains (or cyclic aliphatics) while low –CH2–/–CH3 imply the aliphatics are branched.

What complementary chemical and spatial information does scanning transmission Xray microscopy (STXM) provide relative to FTIR when characterizing N- and O-rich organic phases in asteroid regolith?

There are two parts to this question: spatial and chemical. Spatial, STXM provides chemical bonding information down to very small spatial values (nm range), while the FTIR technique using typical IR microscopes (like the one in my laboratory) is limited to measuring whole particles and has spatial resolutions measured in μm. Our paper does contain some nano-FTIR data take at the Advanced Light Source that has much higher spatial resolution, but most of our IR spectroscopy was done on a more conventional IR microscope. The IR microscope has the advantage that it allows for rapid discovery and characterization of whole particles, while the STXM provided the advantage of providing much better physical context to the internal composition of the samples. Spectrally, both techniques provide comparable information regarding chemical bonding, although the sensitivity of the two techniques can differ for specific chemical species. There is a significant advantage to using both techniques, because the data from each technique can be used to help interpret the data from the other. Spectral techniques occasionally have problems with spectral confusion; for example, bands can appear at positions that could be indicative of more than one type of bond, but it’s unusual for both FTIR and STXM to have the same two bond types overlap in both sets of spectra, so one data set can often eliminate potential degeneracy in the identification of a band in the other data set. In our recent paper, we were able to use this advantage to help determine that one of the bands seen in the FTIR data was not primarily due to nitriles. Finally, STXM spectra can be used to estimate the relative elemental abundances of C, N, and O by fitting the spectra with the atomic mass absorption coefficients, which is not possible to do with IR spectra.

How can N-edge and O-edge X-ray absorption spectra be used to differentiate amines, amides, N-heterocycles, carbonyls, and hydroxyl functionalities in complex organic solids?

As an example, if we see an amine (C–NHx, no oxygen), we expect it to show up mostly in the carbon spectra and not in the oxygen spectra. Amines also show up in the nitrogen spectra, but because of orbital symmetries, the features that indicate amines are weak and hard to see. On the other hand, if it is an amide (C=O)NHx, then the orbital structures are different and we expect the feature in the carbon XANES spectra to move, as well as a clear peak in the nitrogen spectra. Similar circumstances are present for many of the other specific chemical groups. While IR and STXM both have specific blind spots, when combined they tend to complement each other.

What are the advantages and limitations of secondary-ion mass spectrometry (SIMS) for measuring nitrogen isotopic compositions (δ.⁵N) in micron-scale extraterrestrial organic materials?

One of the chief advantages of SIMS measurements of N (or any other element for that matter) is the techniques relatively high spatial resolution. This allows you to obtain data from small areas within your sample without the signal being “polluted” by counts from adjacent materials. In terms of limitations, if a sample is too small, you may not be able to get a good measurement due confusion caused by counts from adjacent materials or there may simply be insufficient material available to get a good measurement. Depending on the element being measured, there are often issues associated with molecular interferences, such as matrix dependent effects, which can be substantial. Making these measurements on small scales requires considerable skill and knowledge.

Why is multimodal spectroscopy (FTIR, STXM, SIMS) critical for confidently identifying polymeric organic phases in returned asteroid samples, rather than relying on a single spectroscopic technique?

As noted in the response to Question 2, the two spectral techniques can provide information that supports and disentangles bond identification. Using multiple techniques also allows you to correlate data and address questions that lie outside the data of any single technique. For example, using the spectral techniques of STXM and FTIR along with SIMS allows one, in principle, to look for correlations between chemical bonding and isotopic values, information that can provide major clues to the origin of the both the samples and the processes by which the isotopic ratios were produced.

How do spectroscopic signatures support the inference that carbamate-derived polymers formed at cryogenic temperatures prior to the melting of water ice on Bennu’s parent body?

The production of the carbamate was a required first step in making the polymers. Since carbamates aren’t stable in liquid water, and there is abundant evidence for the presence of liquid water in the early history of Bennu, this means that the polymer had to begin to form before liquid water was present on the Bennu parent body, i.e., before the H2O ice melted. This requires the chemistry occur early at cryogenic temperatures.

What spectral evidence distinguishes polymeric organic matter from soluble organic compounds in carbonaceous asteroidal samples, and how does this distinction inform formation pathways?

Our polymeric material has a unique IR spectrum which distinguishes it from the distinct soluble organic compounds detected in Bennu samples. However, the spectrum itself doesn’t tell us our material was soluble or insoluble. To establish that, we had to give a sample of our material a “micro-bath” to see if it dissolved, which it didn't (this is discussed in the paper). This provides some information about chemical pathways; for instance, the fact that our material is insoluble means that it could form early in the history of the parent body, didn’t need water to form and could then survive through subsequent exposure to liquid water. The soluble phases seen in the samples would clearly have been affected by the later presence of liquid water, which had to have played a role in the formation and alteration of these compounds. This makes it clear that our insoluble material and the soluble organics were created by different chemical processes (although they both shared the same initial reservoir of starting materials).

How can infrared absorption bands near 3.1 μm and 3.4 μm be used to infer the presence of ammonium salts, N–H functional groups, and aliphatic hydrocarbons in asteroid surface and returned-sample spectra?

These bands have already been used to detect some of these chemical function groups on other bodies in the Solar System, for example, Ceres and Bennu (see [2] for a discussion of the detection of C–H groups on Bennu made using the spectrometers onboard OSIRIS-REx).

How does isotopic fractionation observed by SIMS complement molecular-level spectroscopic data in reconstructing the chemical and thermal history of extraterrestrial organic matter?

It’s a complicated story which meteoriticists are still trying to sort out. The presence of isotopic fractionation tells you something about the nature of the molecule precursors involve in making extraterrestrial organics. The enrichments of D and 15N seen in many organics suggest that the likely precursors (such as H2O and NH3) probably formed in cold interstellar or protostellar environments and the precursors were carriers of the enrichments. The fact that these anomalies weren’t subsequently “washed out” by subsequent chemistry places some constraints on how much chemistry occurred, after the compounds were made, but before the products were sequestered in the parent body. Our polymers are quite unusual in the sense that they show unusually light N, while most isotopically anomalous organics in extraterrestrial materials contain heavy N. Seeing the light N values in our polymers was a wonderful thing for us since the presence of unusually light N indicated that (i) the material was, in fact, extraterrestrial; and (ii) it supported the idea that the chemistry that made it probably occurred at cryo-temperatures where kinetic effects would dominate the reaction process and favor light N.

What challenges arise in interpreting spectroscopic data from heterogeneous, finegrained regolith materials, and how do spatially resolved techniques such as STXM and TEM mitigate these challenges?

With μFTIR spectra, you get the spectrum of whole particles. This allows you to determine the relative abundances of various chemical groups present in the sample, but in heterogenous, fine-grained materials like the Bennu samples, this generally doesn’t tell you too much about how the groups are arranged relative to each other. Some of the groups you see may reside together in the same molecules, or they may be in separate molecules. At higher spatial resolutions, you tend to decrease the mixing of spectral bands due to different materials, which helps with this problem, although in the sorts of material we look at, the heterogeneity often exists at even the smallest scales. Establishing which “family” of absorption bands belong to the same materials often requires the measurement of multiple samples that have different mixing ratios of spectral components. One can then look for bands that rise and fall in strength together. For example, Figure 1 in our paper shows the spectra of three particles that have different proportions of our polymeric material relative to minerals like phyllosilicates and

carbonates. By seeing which bands maintain similar strength ratios in all the spectra, and which don’t, it was possible to establish which features belonged to our polymeric material and which didn’t.

References

1. Sandford, S. A.; Gainsforth, Z.; Nuevo, M. et al. Nitrogen- and Oxygen-Rich Organic Material Indicative of Polymerization in Pre-Aqueous Cryochemistry on Bennu's Parent Body. Nat. Astron. 2025, 9 (12), 1803-1811. DOI:

2. Kaplan, H. H.; Simon, A. A.; Hamilton, V. E. et al. Composition of Organics on Asteroid (101955) Bennu. A&A 2021, 693, L1. DOI:

Newsletter

Get essential updates on the latest spectroscopy technologies, regulatory standards, and best practices—subscribe today to Spectroscopy.