- January/February 2026

- Volume 41

- Issue 1

- Pages: 12–18

The Synergism Between Raman and ATEEM for Characterizing β Amyloid Insulin

Key Takeaways

- Amyloid fibrillation can be tracked by ThT fluorescence, but binding reflects β-sheet–rich motifs broadly, supporting use in monitoring intermediate steps toward fibril maturation.

- Drop-coating deposition Raman exploits “coffee-ring” fractionation to isolate protein signal from buffer, enabling band-fitting of Amide I components for secondary-structure estimation.

This column will show Raman results and ATEEM fluorescence whose correlations indicate that important information is available non-destructively.

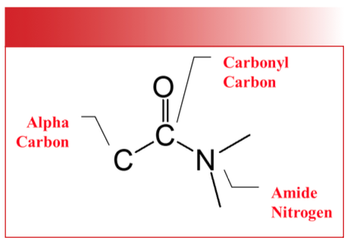

The use of insulin injections to control one’s blood glucose level provides life-saving control for patients with diabetes. In its native state, after proinsulin is converted to insulin by cleavage and formation of three disulfide bonds, the insulin is stored in the pancreas as a hexamer that is stabilized with two zinc ions. When needed (because the glucose level in blood rises) insulin is released from the pancreas into the blood stream and disassociates into monomers which are the biologically active forms. Pharmaceutical companies have engineered modified insulins in order to optimize its control time by making point changes to a few amino acids. However, maintenance of the insulin in its active form is of prime importance because modification of insulin (or almost any protein) can cause aggregation into non-active or toxic forms. For these reasons information on the physical-chemical form of the molecules is of prime importance to the pharmaceutical corporations who are manufacturing these products and selling them to patients. It is known that degraded insulin forms amyloid fibrils that are high in β sheet protein structure. This column will show Raman results and ATEEM fluorescence whose correlations indicate that important information is available non-destructively.

The focus of the pharmaceutical industry is in the detection of degraded insulin, especially in its fibrillar phase. However, there are intermediate changes that occur before the protein aggregates into the fibrillar phase. Various methods such as heat, chemicals (for example acid solutions) and shearing have been used to degrade insulin, after which the formation of fibrils can be documented. The formation of fibrils can be monitored semi-quantitatively by measuring the fluorescence of ThT (thioflavin T) fluorescence which is considered the gold standard for detecting and quantifying the presence of amyloid fibrils (1). These authors also show specific changes in the Raman Amide I signature to the protein backbone that is known to be associated with aggregation, as well as a band near 940 cm-1, indicative of a non-amide helical signature that increases for a while and then disappears in the final fibril phase. The microscopic structure of the fibril is described as a crossed β sheet where the α helical backbone is converted to β sheet which is oriented normal to the axis of the filament.

Raman Analysis

The Amide I part of the Raman spectrum has been separated into at least 2-3 components over the years (2) and band-fitting of the spectra enabled estimation of the structural composition. However, the best publication that I have seen on the assignments of the components of the Amide I band is in a recent publication from Bristol Myers Squibb (3). The group under Ravi Kalyanaraman has calibrated the band-fitted components of the Amide I band of a group of proteins exhibiting a variety of known XRD (X-ray diffraction) structures. Using PLS (partial least squares, a Multivariate Analysis method) they were able to predict the percentages of the Amide I components in the Raman spectra to better than 1.5% accuracy. They subsequently confirmed the prediction of percentages of Amide I components in a second set of proteins with known XRD structure. They shared with us the frequency ranges of the six recognized structures that are listed in Table 1. Note that this table, which shows a range of frequencies for each secondary structure, has not yet been published by the Bristol Myers Squibb group.

A good early reference showing the power of the assignment of the β-sheet to fibrillation comes from the group of Paul Carey who has been reporting the Raman spectra of proteins for many years (4). In this 2006 publication his group studied the effects of changing the disulfide bridges on the formation of β-sheets. In this article they were even able to argue that the “danger of fibrillation has imposed a constraint on protein evolution.”

Our Raman spectra were acquired using the DCDR (drop coating deposition Raman) where a small droplet of protein-containing solution is deposited on a hydrophobic slide and allowed to dry (5). Because the protein is the largest molecule, and therefore the least soluble, it drops out of solution first leaving a “coffee ring” deposit. The buffer and any other small molecules in the solution usually deposit inside the coffee ring so that the spectrum, when acquired from a micrometer-sized spot in the coffee ring, contains only that of the protein. It has been established that the spectrum of the dried deposit is identical to that of the protein in solution (6). Note that in a separate communication with Kalyanaraman he indicated that under some conditions the small molecules will co-deposit with the protein, but that was not the case here.

ATEEM Analysis

Our goal in this column is to determine if ATEEM can be useful for following insulin degradation without the use of an added dye. There are two issues to be addressed. Does the ATEEM fluorescence follow fibrillation specifically? Is there an ATEEM signature that can be used to follow fibrillation without the use of an added dye? Figure 1 shows our ATEEM spectra of the ThT kinetics. While there is clearly a ThT signature in the insulin sample and it is increasing with exposure to the shearing rotation, it is known that ThT is not specific to fibrils but rather to β-sheet rich structure motifs and thus could be used to track the fibrils’ formation process (7).

Figure 2 shows the ATEEM spectra of a peptide that was known to be fibrillated. The analysis points of the aromatic amino acids are noted in the lower left—all data appear at wavelengths less than 250 nm. Unfortunately, in order to capture the degradation of the insulin, the signature from the aromatics could not be included in our measurements shown below because they are so intense that they overwhelm the signal from the degradation of the insulin. This may be important because, as we will see below, our Raman spectra show changes in the relative intensities of the aromatic amino acid bands in different states of degradation, and this has been reported in the literature for linear fibrils vs spherulites (8). In the studies in this column ATEEM spectra will be shown between 325 and 650 nm (the yellow box in Figure 2).

Figure 3 shows the ATEEM spectra of human insulin with the addition of ThT at the beginning of stress on the left and highly stressed on the right. Circled regions show the spectral regions that change. The region between 525 and 600 nm has the higher intensity change.

Figure 4 shows the ATEEM spectra of two commercially available insulins. The one of the left was 9 years expired and shows the stress signature between 525 and 600 nm. The one on the right has not yet expired and its ATEEM signature appears quite similar to that on the left side of Figure 3.

Now let us look at the Raman spectra of human insulin—stressed vs. unstressed. The spectra that we will show were acquired with 638 nm laser. When we excited with 532 nm we found that the stressed sample fluoresced. Note that fluorescence in the Raman region when exciting at 532 nm is consistent with the ATEEM fluorescence that was observed between 525 and 600 nm! Figure 5 shows the Raman spectra between 400 and 1750 cm-1 of the fresh vs the old insulin samples after scaling so that the strong phenylalanine band near 1000 cm-1 had the same intensity in both spectra. (These spectra were acquired from the same samples whose ATEEM spectra are shown in Figure 3.)

When examining these results, what is curious is that their largest changes are in the region between 1500 and 1620 cm-1; the bands here are assigned to tryptophan and tyrosine (9). This was an unexpected result. We were hoping to see evidence of fibril formation which would have been manifest in the growth of the β sheet band near 1670 cm-1. However in reviewing the literature to which we have access we saw that Professor John Carpenter also noted that the tertiary structural differences which he saw in his samples of fibrillar insulin were more related to the relative intensities of the aromatic amino acids than changes in the Amide I region (8). In addition, Carpenter and his collaborators focused on the region between 800 and 875 cm-1 where the relative intensity of two bands of the tyrosine Fermi resonance doublet is different in the two stressed samples that he examined. The relative intensity of this doublet has been related to hydrogen bond donor and acceptor status making this another spectral feature that can be used to assess the tertiary structure of insulin (8). Figure 6 presents an enlarged view of this region for our spectra. In our spectra, two peaks were band-fitted (Figure 6b), and the ratio of their integrated areas is not significantly different between samples. While we have not observed any differences in this region, it is useful to know that this is another spectral feature that can be used to characterize the state of insulin.

Figure 7 shows the region between 1500 and 1800 cm-1 band-fitted to the α helix (~1658 cm-1), the β sheet or turns (~1685 cm-1), the tyrosine band (1615 cm-1), the phenylalanine doublet (~1583 and 1604 cm-1) and tryptophan (~1565 cm-1) as well as a broad band also near 1605 cm-1. The biggest difference between the two spectra is the broad band under the aromatic bands near 1600 and 1615 cm-1. While this band could be interpreted as a carbon signature, that would require that the other carbon band at 1330 cm-1 would be present, but it is not. (note that with 638 nm excitation the carbon D band falls at 1330, not 1360 cm-1).

The last spectral feature that I want to call attention to is the disulfide band near 515 cm-1 (Figure 8). It does appear quite similar in the full spectra but when expanded one can see clearly that there is a broadening on the high frequency side of the center. According to the literature the band near 515 cm-1 is assigned to the GGG (all gauche) conformation around the -C-S-S-C- but a shoulder on the high frequency side is assigned to the TGG (trans gauche gauche) conformation. Again, this is a marker for a subtle change in tertiary structure of the insulin even though the β sheet of the fibril is not detected in our spectra.

Discussion and Summary

We have examined the ATEEM and Raman spectra of insulins in different states of degradation. The ATEEM spectra were recorded without the ThT which, in the past, has been used as a marker of amyloid formation. ATEEM indicates that there have been changes to the protein and Raman provides some insight into the details of what the changes are. We (LC and FXX) will be doing more detailed studies of insulins in various states of degradation in order to determine if these spectroscopies can provide more reliable understanding of what is happening. This information should be helpful to the pharmaceutical companies that are manufacturing insulin for diabetic patients.

References

- Dolui, S.; Roy, A.; Pal, U.; Saha, A.; Maiti, N. C. Structural Insight of Amyloidogenic Intermediates of Human Insulin. ACS Omega 2018, 3 (2), 2452–2462.

https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.7b01776 - Tuma, R. Raman Spectroscopy of Proteins: From Peptides to Large Assemblies. J. Raman Spectrosc. 2005, 36 (4), 307–319.

https://doi.org/10.1002/jrs.1323 - Peters, J.; Jin, C.; Luczak, A.; Lyons, B.; Kalyanaraman, R. Machine Learning Enabled Protein Secondary Structure Characterization Using Drop-Coating Deposition Raman Spectroscopy. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2025, 259, 116762.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpba.2025.116762 - Huang, K.; Maiti, N. C.; Phillips, N. B.; Carey, P. R.; Weiss, M. A. Structure-Specific Effects of Protein Topology on Cross-β Assembly: Studies of Insulin Fibrillation. Biochemistry 2006, 45 (34), 10278–10293.

https://doi.org/10.1021/bi060879g - Ortiz, C.; Zhang, D.; Ribbe, A. E.; Xie, Y.; Ben-Amotz, D. Analysis of Insulin Amyloid Fibrils by Raman Spectroscopy. Biophys. Chem. 2007, 128 (2–3), 150–155.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpc.2007.03.012 - Ortiz, C.; Zhang, D.; Xie, Y.; Ribbe, A. E.; Ben-Amotz, D. Validation of the Drop Coating Deposition Raman Method for Protein Analysis. Anal. Biochem. 2006, 353 (2), 157–166.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ab.2006.03.025 - Biancalana, M.; Koide, S. Molecular Mechanism of Thioflavin-T Binding to Amyloid Fibrils. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Proteins Proteomics 2010, 1804 (7), 1405–1412.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbapap.2010.04.001 - Schack, M. M.; Dahl, K.; Rades, T.; Groenning, M.; Carpenter, J. Spectroscopic Evidence of Tertiary Structural Differences Between Insulin Molecules in Fibrils. J. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 108 (7), 2871–2879.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xphs.2019.04.018 - Kitagawa, T.; Hirota, S. Raman Spectroscopy of Proteins. In Handbook of Vibrational Spectroscopy – Applications in Life, Pharmaceutical and Natural Sciences; Chalmers, J. M., Griffiths, P. R., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2002, pp. 3426–3446. ISBN: 0-471-98847-2

Articles in this issue

about 1 hour ago

The 2026 Emerging Leader in Atomic Spectroscopy Awardabout 2 hours ago

The Big Review VIII: Organic Nitrogen CompoundsNewsletter

Get essential updates on the latest spectroscopy technologies, regulatory standards, and best practices—subscribe today to Spectroscopy.