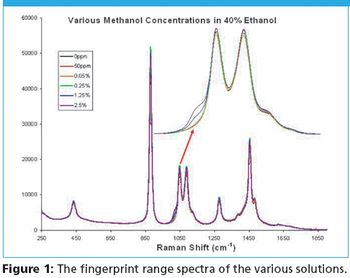

Low concentration natural methanol exists in most alcoholic beverages and usually causes no immediate health threat.

Low concentration natural methanol exists in most alcoholic beverages and usually causes no immediate health threat.

Columnist Fran Adar discusses applications for Raman and FT-IR spectroscopy.

The authors discuss the use of vibrational spectroscopy to differentiate an authentic article from a counterfeit one throughout a product's lifecycle, from component receipt at the site of manufacture, to product receipt by the end user.

The authors discuss the combined use of Raman and FT-IR spectroscopy in fields such as forensic science, biomedical science, catalysis, and polymers.

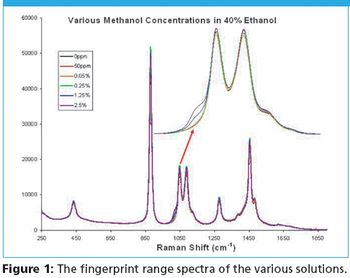

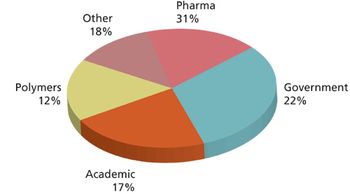

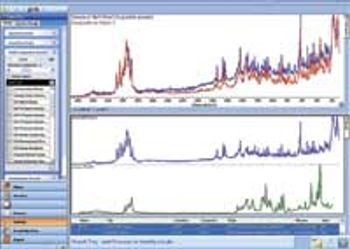

Infrared (IR) spectroscopy and Raman spectroscopy are very complementary methods. The strongest demand tends to come from applications that require analytical information from a potentially broad range of compounds and functional groups. The global market for combined Raman and FT-IR accounts for a small but growing percentage of both the broader IR and Raman spectroscopy markets.

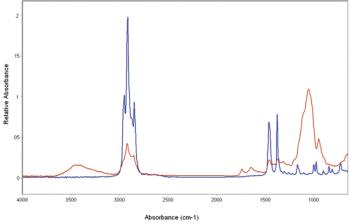

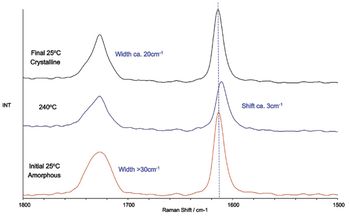

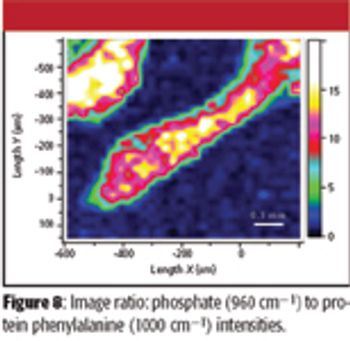

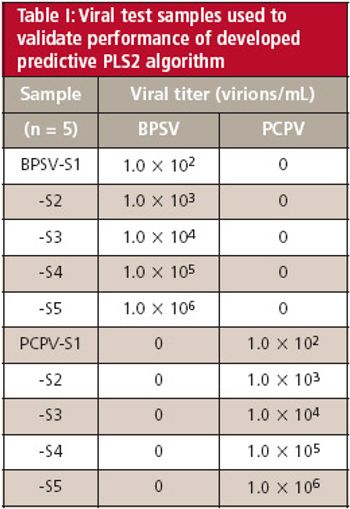

Manufacturing control of pharmaceutical solids requires routine measurement of content uniformity. Because of the high information content in Raman spectra, it has been considered a candidate technology for making these measurements.

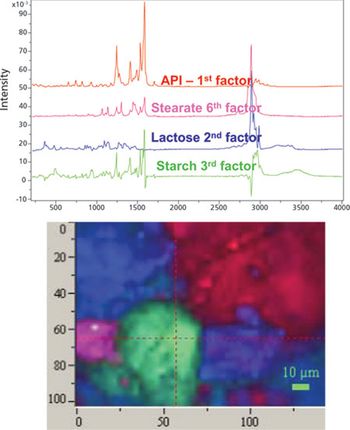

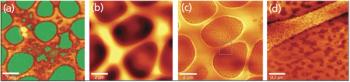

Polymer blends are designed to address the needs of different industries, and in many cases the relationship between structure, morphology, and material properties is indispensable for optimization of material design.

Raman spectroscopy and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) are powerful techniques in their own right. Combining the two techniques allows one to combine the chemical and structural information of Raman with the temperature and energetic information of DSC. This allows us to develop a greater understanding of the material. Applications from polymeric and pharmaceuticals are discussed as examples of how this can help the analyst.

The authors discuss the use of a field-deployable Raman instrument for rapid identification of chemical and biological pathogens.

Miniature spectrometers revolutionized the spectroscopy market more than 15 years ago and became a key factor in the creation and steady growth of the photonics field. Today these spectrometers are becoming an important part of the new market of field-deployable analytical instruments used for materials identification based on Raman spectroscopy. Just as before, these spectrometric photonic engines are key factors on reducing the cost and improving the flexibility of applications of a traditionally expensive and rigid vibrational spectroscopy method. Raman spectroscopy is becoming an affordable tool used for applications ranging from homeland security to green energy research and development, either at a laboratory, a crime scene, or a biodiesel manufacturing facility.

There are many situations in which it would be highly desirable to apply the benefits of Raman to larger volumes of solid material such as powders, tablets, and composites. Raman benefits such as minimal sample preparation, the ability to provide rich information on both organics and inorganics, and its ability to measure through glass and plastic packaging make it highly amenable to these kinds of samples.

New research being conducted at the University of Arkansas is demonstrating that Raman spectroscopy can be used to detect and monitor circulating carbon nanotubes in vivo and in real time.

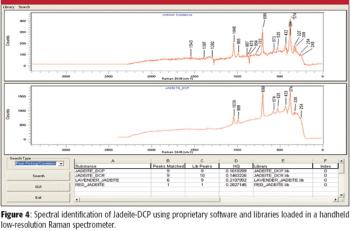

The authors discuss the use of Raman spectroscopy to identify an unknown gem or mineral sample or to verify that a known sample has been classified correctly.

This article discusses instruments that can be used in the field to rapidly and accurately identify various explosives and their precursors.

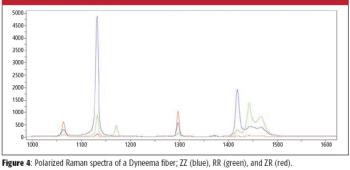

In this article, columnist Fran Adar will review the important features of the Raman spectra of these materials and indicate why the extracted information is important for material development and engineering.

Columnist Fran Adar discusses the physical determinants of spatial resolution and developing methods to improve the mapping speeds of Raman images.

The authors discuss the use of instruments that combine FT-IR and Raman microscopy on a single platform, enabling synergistic studies of many materials.

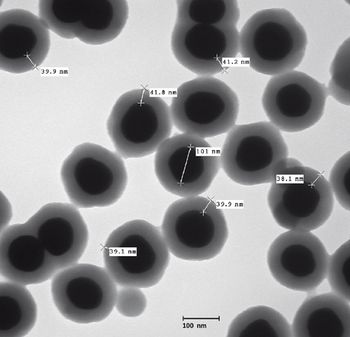

Surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) has experienced an explosive resurgence in interest lately. Development of reproducible, spatially uniform SERS-active substrates has made this technique an attractive approach for identification of Raman-active compounds and biological materials including toxins, intact viruses, and intact bacterial cells–spores...

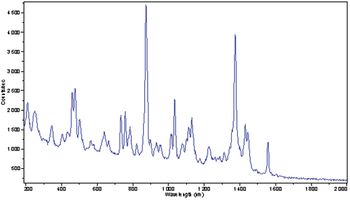

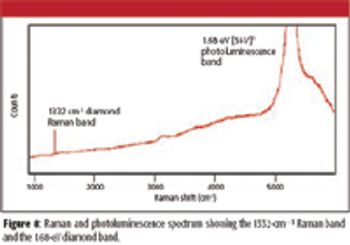

Raman spectroscopy is going through a major revolution with the continuous introduction of new fiber-based modular systems for low-resolution applications. More and more scientists are discovering what Raman spectroscopy can do for their research, education, and commercial applications thanks to the low costs and flexibility this new technology is providing. New applications and prospects are presented each day, and it is important to understand the advantages and limitations that this user-friendly analytical technique can provide to address these opportunities with a scientific approach.

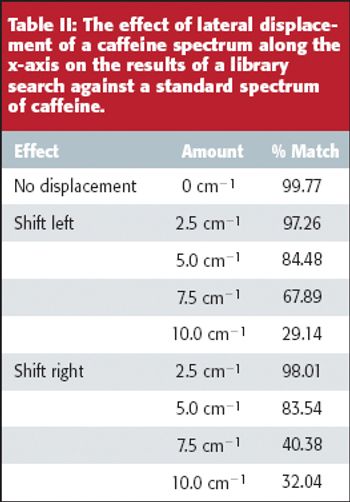

Over the last few years, Raman has made the transition from a technique used solely in a research environment to one that is now seen as a powerful tool for routine analytical use. Raman spectroscopy now is used widely for sample identification in fields as diverse as forensics, QA/QC, art conservation, defect analysis, and failure analysis. This has imposed new demands on the technique for reproducibility and stability. Successful sample identification takes advantage of the extensive spectral libraries and sophisticated search algorithms that have been developed in recent years. However, in order to be able to cross-correlate experimental and library spectra with any degree of confidence, it is critical that the Raman spectrometers used to collect the spectra are calibrated rigorously. It is likewise critical for QC applications that spectra collected on one instrument can be compared reliably with spectra collected on other instruments and that results remain constant when collected over extended periods..

Raman imaging has moved on. It is now possible to capitalize on the wealth of information available from a Raman spectrum by imaging materials over large areas, with the spatial resolution, spectral resolution, and laser excitation parameters tailored to suit each application. Raman experiments and images from a diverse range of samples are presented.

Chemical analysis in the forensic field is different in many aspects from other areas of analysis. The ultimate goal is to identify the sources of evidence, often by matching chemical composition. In this regard, identifying minor elements or trace impurities is as important as identifying main ingredients. In some cases, identifying minor and trace components can be critical to determining that material collected at the site of a crime is identical to material collected in a suspect's environment. In other cases, full identification of trace evidence can be important. Raman microscopy is capable of providing both types of information on minute amounts of material.

Since it was first described in 1974, surface-enhanced Raman spectrometry (SERS) has been thought to offer significant potential for a range of different applications. The theoretical sensitivity and specificity envisaged for this powerful technique has engaged scientists for many years, but practical challenges have hindered its routine adoption. Now, a new approach combines a robust and reliable substrate with expertise in surface chemistry and molecular biology on a platform that can be adapted for a wide variety of Raman instrumentation and customized routine applications.

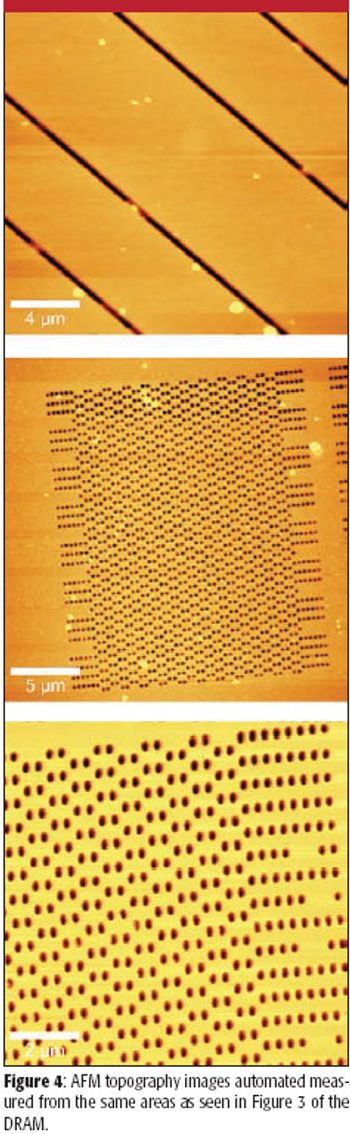

The combination of confocal Raman and atomic force microscopes allows chemical and surface topography imaging of large samples without any ongoing process control by an operator. This article describes the relevant measurement principles and presents examples of automated measurements on nanostructured materials.

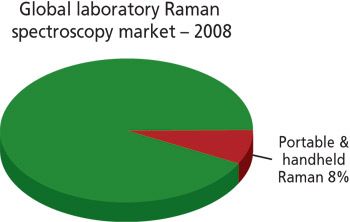

The continuing pace of technological advancements in scientific instruments has recently led to a wide range of commercially viable portable and handheld instruments, and the Raman spectroscopy market is no exception. While security applications have received much of the early attention in relation to handheld instruments, other applications are beginning to replace demand from the security markets.